In the spring of 1988, not long after the Calgary Olympic Games ended, Kim Cairns moved to the west coast with his partner, a psychologist hired to run women’s studies programs at the U of BC. Kim did contract work for the Boys and Girls Club. When he heard about a John Howard Society’s Request for Proposal seeking a consultant/trainer, he forwarded the RFP to me to see if I’d be interested.

The Society focused on assisting individuals who are exiting the criminal justice system. Their RFP stated they planned to institute a five-month program to help clients build career skills, find employment and housing, and reintegrate into society.

They needed a consultant/trainer to design a 30-day outdoor challenge program as the kickoff element of the five-month program. And to design and run a five-day training program for staff who would run the outdoor piece.

I wrote a proposal suggesting a kind of Earthways and Wilderness One program for adults. It would include short and long hikes, bouldering and rock climbing, canoeing skills, and a three-day solo.

Activities would help participants develop the high level — generic — Creating and Experience-Action Skills they would need to rise to their re-entry challenge. Other parts of the five-month program would help them develop specific life/work skills.

The Society invited Kim and me to present to their board in Victoria. I flew to Vancouver and stayed with Kim for four nights. We fine-tuned the proposal and our presentation, reminisced about our Camp days, and talked a little “stuff.”

On the fourth morning, we flew to Victoria, then did a presentation. My heart fluttered and my head hurt. Part nerves, but mostly excess beer the night before. But we got the contract.

I spent June on the west coast, subletting an apartment from two Banff Centre artist/teachers who had taken my Creating course in Calgary. Kim and I ran the John Howard program successfully. I searched for a place to live, and out of which I might run workshops and coaching sessions.

Shocked by the high cost of housing in Vancouver, I almost gave up. But, near the end of June, I found an affordable two-bedroom-with-den duplex on East Boulevard, just off the upscale Kerrisdale district’s commercial strip.

I sold my Calgary cottage for $10,000 more than I paid for it, then moved to Vancouver.

*

Eager to duplicate my Cowtown workshop, coaching, and retreat successes, I jumped into my west coast Free Lance venture with both feet.

I made the large bedroom off my duplex’s entrance alcove into my office. I spent a sizeable chunk of cash outfitting it and my rectangular living room with professional looking Ikea furniture. Between my living room that could seat 10 workshop participants and the kitchen, I used a small dining nook as a materials library and refreshment bar for participants. I slept in a cozy — quiet! — roughed-in basement bedroom with a raised wooden floor. I set my TV on Ikea shelving.

I tingled with adrenaline rushes, anticipating the challenge of applying all I had learned to this exciting new venture. Things were unfolding as then should.

Then I slammed headlong into a wall.

*

Two setbacks tried my hard-won Free Lance confidence.

At the end of my first week in my new digs, I charged through Pacific Rim Park on my bike, thinking, “this is a breeze compared to mountain trails.” But, when I swerved to avoid an over-hanging bush, my wheel caught in rough washboard and threw me over the handlebars.

When I tried to remount my bike, I almost passed out from shooting pain in my right shoulder. Shocked, shaken, and scared, I started pushing my bike to the trailhead. Tears rivered a path through the dirt and blood on my face.

Luckily, a couple riding toward me stopped.

“Are you okay?” the man asked.

“No,” I said. “I think I’ve broken something. I can’t ride.”

He rode off to get his car from their nearby home. The woman walked with me to the parking lot. They loaded my bike into their Volvo station wagon, then drove me to UBC Hospital’s emergency room. Gave me a $20 bill for cab fare. Told me to call them when I was ready for them to bring my bike to my home. Their kindness brought more tears.

I sat alone and hungry in the ER waiting room as the sky darkened, sharp pains shooting through my shoulder if I so much as tensed my right arm. A brusque ER doc fitted me with a harness-like, figure-8 clavicle support brace and a sling. And wrote a prescription for codeine painkillers.

But the brace’s harness was so tight it peeled the skin off my underarms.

In the days before and during the John Howard program, and each morning for weeks after, Kim had to tape sterile gauze dressings over my wounds. I suffered constant pain, despite the codeine. But we finished the outdoor challenge program and received high praise from participants.

*

After the John Howard program, I suffered a nasty canker sore outbreak similar to the majour one I had endured in Canmore.

A family doctor diagnosed “familial leukopenia” — an inherited condition of chronic low white cell counts. He thought the stress of my move and accident caused my canker sores. He suggested over-the-counter canker/cold sore medications. They helped with pain, but did nothing to prevent recurrences.

During a follow-up visit later, the doc suggested I track my food, exercise, stress, sleep to see if I noticed a connection with the sores.

I discovered that almost every time I pushed myself hard — jumped my normal 60-minute bike ride to 90 minutes, tacked on an extra mile or two to a five-mile run, or ski hard for two or three days at Whistler — I would experience a mild to nasty bout of canker sores. They lasted 10 to 14 days, and usually made me feel as if I had a low-grade infection. For 20 years, I felt mild to moderately ill for a third to a half of every month.

Then, I met a woman whose doctor recommended Lysine supplements. They worked. I’ve been almost canker free since. If an outbreak occurs, I up my Lysine intake from 500mg each day to 500mg every six hours. The cankers usually heal in 2 to 3 days.

*

In Vancouver that first year, after the nasty bout of canker sores had healed, I spent another chunk of cash on high-quality materials promoting Uncommon Sense: Consultants In Personal and Organizational Mastery.

I printed business cards, promo brochures, fliers, and posters, and five-by-eight-inch postcard-style workshop invitations — all on pebbled beige cardstock with burnt orange headings and black text.

One side of the postcard listed course details and provided space for a delivery address. The other featured an inspirational quote. Later, I would sometimes see those quotes displayed on cork boards and kitchen fridges.

But, my first mailing generated four workshop participants. The second only six. My spirts sagged. Anxiety swelled. Dark raptors circled above me.

On reflection, I saw that in my eagerness to relocate to the coast; I had failed to thoroughly assess current reality relative to my Free Lance vision.

I lacked the 200+ natural constituency of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances I had drawn on in Calgary. I also had to vie with hundreds of laid off BC government employees — instant consultants who sought the same clients I did.

I struggled for months, dipping into cash reserves to pay monthly expenses.

With time on my hands, I changed gears. I turned my Taking A Stand for the Earth outline into a 4000-word article.

A friend read a draft, then shared it with his Masters of Environmental Management professor at Simon Fraser University. The prof liked it and asked me if he could add it to his grad and undergrad assigned readings.

He also suggested I turn it into a book.

I laughed. “Yeah, right.”

Through freebie speaking gigs, mini-workshops for non-profits, and two radio talk show appearances, I slowly expanded my reach.

I did small TFC courses with ex-SFU friends and their contacts. I designed and ran a two-day “Creative Dynamics” workshop for a real estate firm.

But, by the end of that year, I was almost out of money.

*

In my second year in Vancouver, I swallowed my Ronin pride.

I took a job with a non-profit “science education” association that needed help to develop a training program for the BC government’s Environment Youth Corps (EYC).

EYC helped unemployed young people develop specific personal, interpersonal, and vocational skills through enhancing the environment and promoting conservation in local communities.

Eight to ten participant teams did trail repair, refurbished picnic and park structures, planted trees and shrubs, and cleaned up parks and campgrounds. An older team leader supervised.

But no one in the association knew how to help participants integrate specific work skills and experience with generic personal mastery skills.

When interviewed, I explained my approach to the director. The short, natttily dressed man hired me but told me he wanted me to create a “unique to us program, from the ground up.”

“Based on science!” he added.

So, for two hundred and fifty dollars a day, four days a week, he had me research personal development programs in the public library. I took the money but almost choked on the futility of the approach.

None seemed based on science. None differentiated between specific and generic skill development.

I did a 1-day creating workshop for association staff. The director didn’t join us, but most who did appreciated it. One young fellow who “got it” would become my partner in later endeavors, and a friend.

The workshop had no effect on the director, or his cocky attitude. He still wanted a “unique” program, but could not provide parameters or guidance.

The Association had already spent $100,000 of BC government funds. When the director told me he was going to ask the government for another $50,000, I went to our Environment Ministry minders on my own and offered to create and deliver a complete program — including three-day workshops and workbooks for EYC teams, another workbook for team leaders, and a train-the-trainers program for $16,000.

They jumped at it.

I left the science association, once again Free Lance, in charge of my own work.

With another chance to implement my own damn system.

For two years, I — and two trainers I brought on board and trained — ran workshops throughout BC.

Most participants liked them. Some more so than others.

One afternoon, as I walked down East Hastings Street, a rough area of east Vancouver, I saw a tall, tough-looking, dark-haired guy coming toward me.

When he saw me, he waved, shouted, “Hey! I got that stuff!”

Not a sentence I wanted to hear in that part of town. So, I crossed the street.

But, when the big guy ran over to me with a wide grin on his face,I realized he had been in a Regional Correctional Centre’s work-release group I’d done an EYC workshop with.

“Youth Corp guy!” he said, taking my hand in a bear-sized palm, “I got all the things from the list I made in your workshop. My pardon. A driver’s licence. A job sodding lawns. And my own room in a shared house. I’m even working on my GED!”

I congratulated him, told him how proud I was. As I walked away, chuckling, I thought, Expect nothing; be ready for anything!

I used the last my savings to fly to Boston and take a new Organizational Technologies for Creating (OTFC)@ course from the Fritz group, and get certified to offer the course.

On my return, I did talks and mini-workshops for businesses and other organizations. Few led to paid work, though some seemed they might later.

I also commuted to Alberta once a month to help John Amatt and a local team run a day-long, outdoor team-building session for Petro-Canada[1] managers. Part of a five-day leadership course run by National Training Laboratories (NTL), a US consulting firm.

The session took place on the Stoney First Nation, in Nakoda Lodge on the site of old Hector. During the last one I did, the consultants gave us all a copy of Max De Pree’s slim paperback, Leadership Is An Art. In it De Pree quoted Oliver Wendell Holmes:

I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity,

but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.

After I read and re-read it, I wondered, Could my approach help people to create and live that kind of simplicity?

*

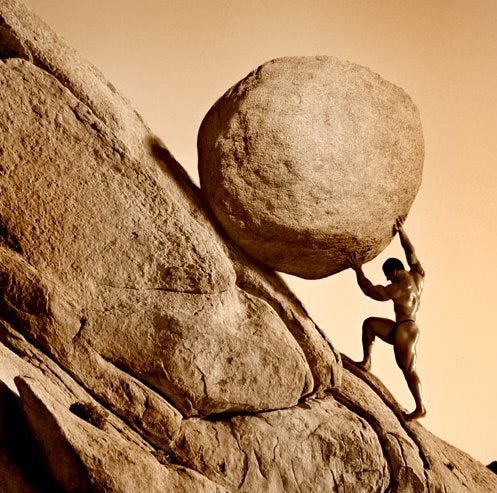

In Vancouver, I nudged my rock uphill . I ran successful half- to three-day workshops for organizations as varied as Motorola, Fisheries Canada, Boys and Girls Club, several universities, and a three non-profits.

Though they paid well, they lacked the heart I longed for.

To clarify my thinking, I reworked my Taking A Stand for the Earth article.

I thought if more of us lived simple yet rich and sustainable lives — in harmony with the ecological systems we depended on — we should be able to create the “simplicity on the other side of complexity” and a minimal ecological footprint.

I reconsidered the SFU prof’s suggestion to turn my article into a book.

Each year since I had read The Path of Least Resistance while working on Ken Low’s Freedom Skills project, I’d made annual lists of results I would love to create.

One night, looking over the previous year’s lists, I noticed a different result — “Bruce’s trip of the year” — topped each.

But, in second place every year, sat “Writer.”

So, I moved ‘A published book’ to the top of my “Desired Results list.

*

Mid-winter in my third year on the coast, I realized I had not had a proper vacation for years.

So, I booked a cottage on Saltspring Island for December, and made plans to take a self-directed “writing retreat.”

My long-term goal had been to become a Free Lance educator, coach, and writer.

I still had a way to go before I realized that goal.

But I thought I was on the right path.

[1] Petro Canada was a federal government owned Oil Company; a Crown Corporation.